The London Palladium is one of the world’s most famous variety seated theatres, flaunting previous acts known far and wide including Harry Houdini, Carmen Miranda and even Laurel and Hardy. After centuries of performances however, this Friday night belonged to one genre of music that never intended to become general consumption but went on to categorise itself under names such as Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Leonard Cohen and Loudon Wainwright III. I am of course talking about folk music.

The floor and middle tier began to systematically become flocked with men and women, young and old, eagerly awaiting the dimming of the lights. They would however, have to patiently wait for the main act as out walked Chaim Tannenbaum, sporting nothing but an acoustic guitar, a harmonica holder, corduroy trousers and a handful of amusing anecdotes.

The subtly comical musician came to London from Canada in the 60’s and fell for the “old bruised city”, comfortably hiding himself away for a number of years of his passion behind a cloak of grandeur that the company he kept wore through years of generations. This cloak however, has become worn with age and adopted tears that Mr Channenbaum has finally decided to peak through and reveal himself as an independent artist.

Dink’s Song (originally a song written by Alan Lomax but recorded with Mr Tannenbaum and the Wainwright family to commemorate Kate McGarrigle) was the first played and gave a firm clasp around the audience’s attention as he went on to play a score of gently soothing but tightly gripping tracks.

The philosophy teacher honed an eloquent lyricism and wavering singing voice with a scratchy weakness that subsequently magnified the delicate nature of his words. They spoke of an emotional response to British culture through harmonious folk ballads, the “corrosive manner of unemployment” and a few favourite locations in the British capital (as well as a few sarcastic comments on wet starving pigeons and Hackney).

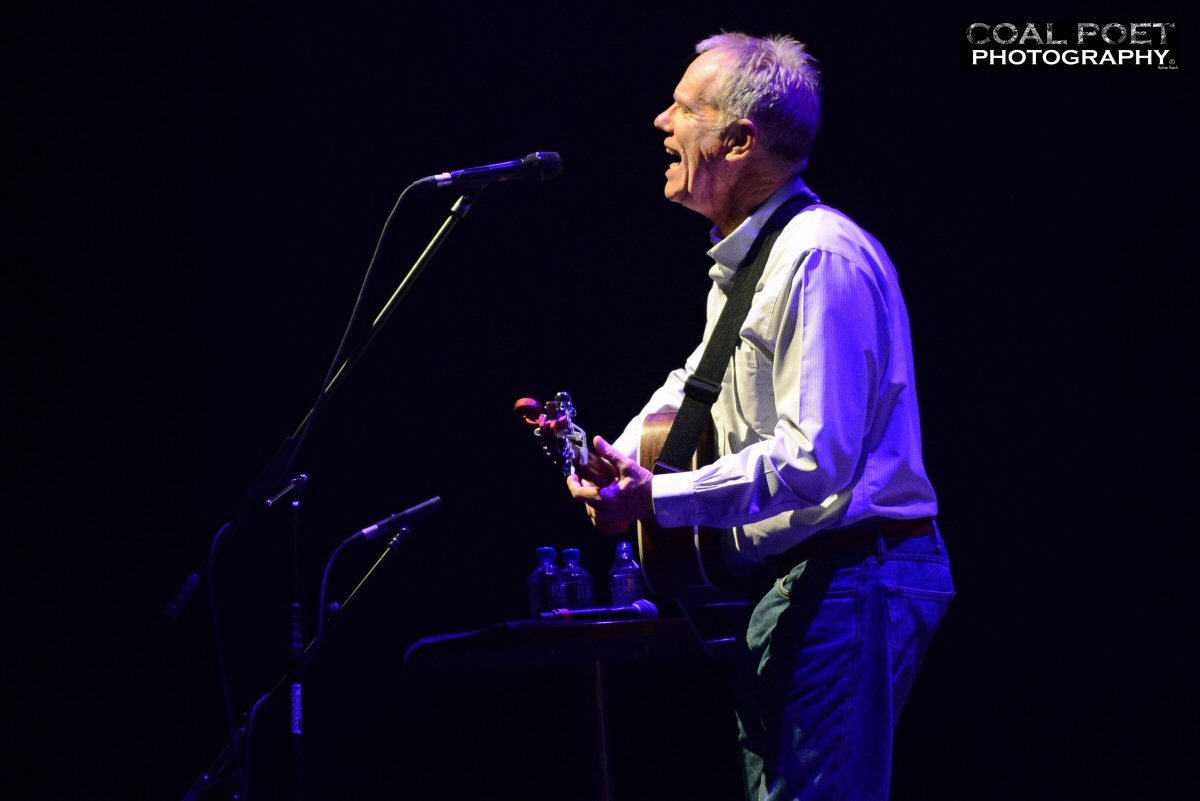

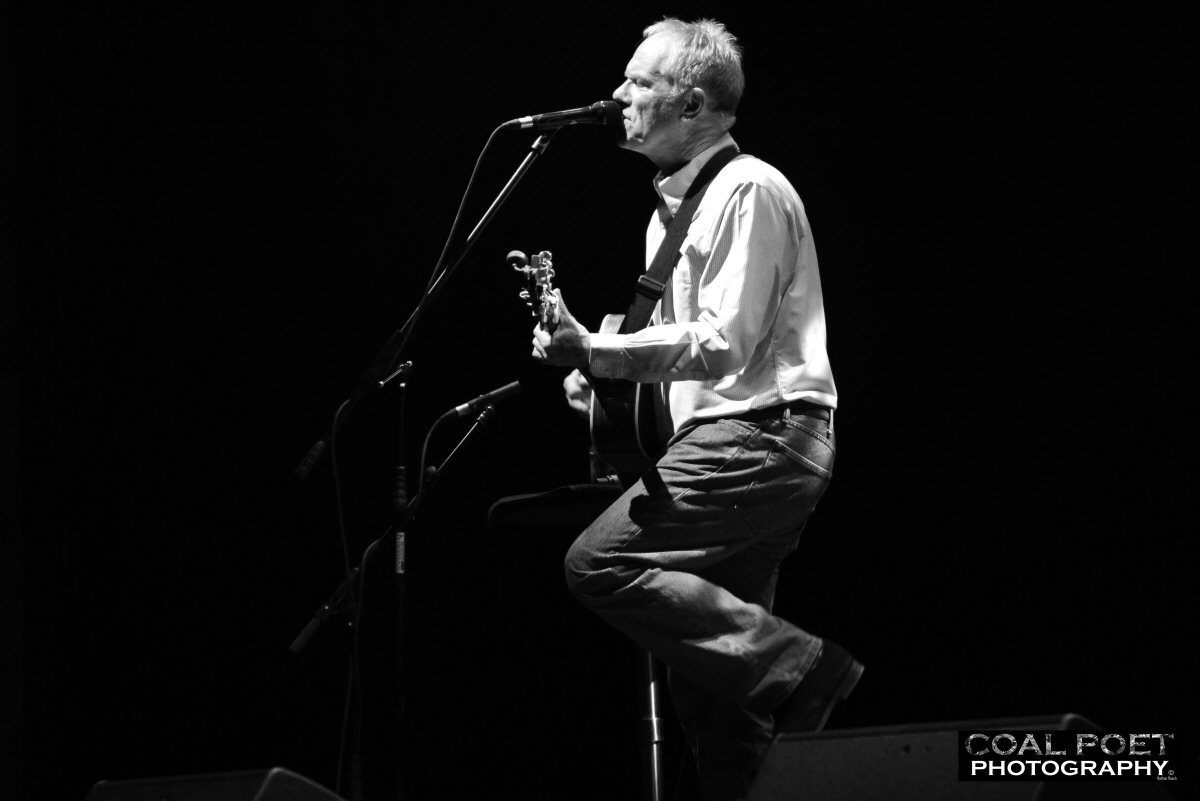

A short interlude satisfied desires for small pots of ice cream and beverage refills before the eccentric Loudon Snowden Wainwright III took to the stage. Recently hitting the big seven zero, it was a warming sight to see that age had certainly not conquered this musician and deprived him of his talent or timeless wit.

“Got a lot of family material for you tonight” he jokingly stated (for anyone who knows the history of his musical relatives) and went on to carry this sense of humour throughout the set with songs such as his interpretation of a beautifully chaotic Heaven, Guilty Conscious and a Broken Heart and a vision of the future (that he sorely hopes will not become fact) titled Trump with a slightly chilling reminder that “sometimes nightmare is reality”.

He beguiled his crowd with a few facts on the previous Loudons and his family. How his father was a column writer in Life Magazine (which he went on to write a few songs about) and his grandfather being quite a mystery but analytically examined through Half Fist. He also highly entertained with a number he had written while playing a score of shows out in Alaska called Meet The Wainwrights, sarcastically gloating about their mixed relationship in the form of a high spirited jingle.

Firmly following the DD of Death and Decay that he has come to accept as his mantra, he explains how close all life is to sorrow and appears to be knowledgeable of false expectations and the bitter reality of life. Be Careful There’s a Baby In The House was written under the impression that a divinity follows fatherhood like an expectation of endless information from someone trusted to know the answer.

Mr Tannenbaum was welcomed back on with his banjo and impressive harmonisations to thicken the already edible atmosphere and to attempt a quick profit on some Bolivian flake cocaine (in relation to their cover of Tom Lehrer’s The Old Dope Peddler). The two had a fantastic symmetry in their quick-fire comedic responses and strong work ethic which had led Loudon to state he was “the most uppity opening act I’ve ever had” and described their relationship as one similar to an Oscar and Felix assimilation.

The Doctor remained a large highlight, where the entire occupants let out a loud and tuneful wail to follow the chorus after some encouragement and emphasised the shows surprising intimacy (in comparison to the vastness of the venue). Audience members became comfortable enough to start requests and Hank and Fred was eventually chosen shortly after stating that “the problem is with requests is I can’t remember half of what I’ve wrote”.

Unusually wonderful to witness, the man has retained his eternal aptitude to verbally illustrate an illustrious narrative over the mundane moments of existence. He exemplified these talents by taking a moment to tell the tale of his dog and his sudden departure from life. This would be distressingly ordinary if told by anyone else but luckily, the true storyteller told a personal story of undisputed love and heartache that left breath slightly withheld with each tiny chapter, ending with an understanding of “the closest I have come to knowing being here and gone”.

Charlie’s Last Song, Unhappy Anniversary and White Winos serenaded the evening into what was supposedly an acoustic chord and banjo plucked finale but instead ushered in an encore that ended in a hair raising a cappella that brought the audience to a standing ovation. The best way to describe the evening would be with one of the headliner’s signature witticisms which was “too old to die young but we can dream can’t we?”